Click! Poof! It’s gone. For many photographers, that iconic “click” signifies the completion of the in-camera photographic capture. As we usher in a new wave of technology, this universally understood audible confirmation is about to go by the wayside.

The electronic shutter is about to supplant the mechanical shutter in yet another case of digital taking over the world. Removing the mechanical shutter eliminates the last major moving parts in the modern camera. In theory it should make all our cameras last a bit longer and I suppose that’s a good thing. However, when was the last time you wore a camera out by firing the shutter too many times?

I’m quite sure that this new electronic shutter will be good for the cameras, but will it be good for photography? That classic “click” is an iconic sound that can both inform and aid the photographer and the subject. There are times where silence is golden; like in theaters, courtrooms, and places of worship, where doing away with any noise is welcome. But in other environments that “click” is an acknowledgment between photographer and subject about the moment they are sharing.

Over the years there have been numerous debates about which camera had the best sounding click. Each camera produced a unique note depending on the type of shutter and body it was in. The solid “klur-thunk” of a Nikon F2 matched the tank like structure of the camera. The subtle and delicate click of the Leica M6 was perfect for street photography. For myself, I was always partial to the mechanical percussion of the Nikon FM2.

Here in the midst of the mirrorless revolution nobody seems to mind leaving the DSLR mirror’s slapping noise, along with the unwelcome vibrations in the past. But witnessing the classic “click” as it makes its way into the history books, makes me wonder if this is really a good thing.

The sound of a shutter clicking brings fond memories to me. Shooting elbow to elbow on the sidelines, listening to the crescendo of clicks perfectly matched with the action on the field. Standing all alone on a beautiful mountain hillside and waiting for the perfect moment, then slowly pressing the cable release until you hear that single discrete “click.” Those were perfect moments for me.

The revolution has started

Today our mechanical shutters are slowly being replaced by electronic shutters. Thanks to advancements in sensor technology, the newest stacked CMOS sensors are able to turn the pixels on, then turn them off, so as to replicate what a traditional shutter would do. A small part of me that resists technological change smiles a bit when thinking that it’s taken 20+ years for the sensor to achieve what was done mechanically more than 100 years ago.

A fast pan with the Sony A9 results in no noticeable distortions.

[Sony A9, Electronic Shutter, 1/3200 sec.]

The modern mechanical shutter is a wondrous little device. It needs to be precise, fast, durable, stable, and fit inside our tiny cameras. It takes two shutters to mechanically “create” a shutter speed. The first one opens the door, and the second closes it. In older cameras this shutter was made of fabric that moved across the long direction of the frame. Unlike a performance stage curtain that opens and closes from the middle, a camera curtain opens from one side, with a second closing curtain that would follow the first.

In order to achieve faster shutter speeds the curtain was replaced by lightweight composite metals that moved top to bottom across the short side of the frame. Each curtain would consist of usually 3 or 4 ultra lightweight blades attached to a small but powerful motor that could start and stop with a minimum of vibration.

With an SLR camera the first shutter would be closed so as to prevent light from striking the film or sensor. When the shutter was released the mirror would rotate up and out of the way, then the blades of the shutter would retract so that light could expose the image area.

At a time determined by the selected shutter speed, the second curtain would begin to close from the other side of the image area. This two shutter system of opening and closing was so that each and every pixel, or silver halide crystal, would be exposed for exactly the same amount of time.

With a mirrorless camera this process needed a small modification. The shutter would start in the open position, so that the sensor could send an image to the viewfinder and monitor. The first shutter would close, the sensor would turn on, then the first shutter would open. After the second curtain would close and end the exposure it would open again so that an image could return to the viewfinder and monitor. In some ways, the mirrorless design doubled the work of the shutter.

Shutter Speeds for Flash

Camera companies have long tried to design the fastest shutter mechanism possible. The primary goal was to have the shortest shutter speed possible. A second goal was to have the shortest shutter speed that could be synchronized with a flash. To record a burst of light, like a flash, the shutter needs to be completely open so that it doesn’t block light from reaching the sensor. The faster you can open and close the shutter, the faster the flash sync speed available. Most camera companies topped out at 1/250th second with flash sync, but a few were able to push a short distance beyond, often with limitations. This remains where we are today with most cameras that have flash sync speeds between 1/200 and 1/250 second. Leaf shutters in special lenses allow for much faster sync speeds, but that’s a different discussion.

Side note: many cameras do offer a way of using flash with very fast shutter speeds, sometimes referred to as high-speed sync. As the shutter exposes a moving slit across the frame the flash fires repeatedly so that all parts of the frame receive the same amount of flash. This high speed sync is not very often used as flash power must be set manually and the distance between the flash and subject is greatly limited.

To achieve shutter speeds faster than the top flash sync speed, the second curtain needs to begin closing before the first is fully open. This creates a moving slit that exposes the image area. The smaller the slit the shorter the exposure time, aka shutter speed. Timing, control and synchronization of the two shutters is key to achieving these fast shutter speeds.

Shutter Speed Arms Race

When I was getting my start in photography there was a bit of an arms race between the camera manufacturers for the fastest shutter speed. Each company was trying to claim some notoriety by outdoing the others in this category. It started back in 1959 with Nikon’s first professional camera, the Nikon F, which had a top shutter speed of 1/1000. In 1971 both the Canon F1 and the Nikon F2 featured a top speed of 1/2000. In 1981, the Nikon FM2 become the first to achieve 1/4000 sec. Nikon extended their lead in 1988 with the N8008/801 which had 1/8000 second top shutter speed. Wanting to have the last word on the subject, Minolta jumped into the game in 1992 with the 9xi which could achieve 1/12000 sec. The competition then moved on to autofocus and who could have the most focus points. Side note: A number of companies now offer electronic shutter speeds up to 1/32000 second.

The Nikon Z9 is the first mainstream digital camera to eliminate the mechanical shutter. I’m sure there is a fair bit of pride at Nikon with another first in this shutter related category. The half step to get to this point was barely noticed with the removal of the first shutter from the Sony A7C and Canon RP. (I’ve not been able to confirm this with the RP, but all evidence points to there being no mechanical first shutter.) Both cameras were designed to be very small and one of the ways of saving some space was to eliminate part of the shutter unit. These cameras use an electronic start to the exposure and complete it with a mechanical shutter. This has long been a feature in cameras with CMOS sensors, often labeled as first-curtain electronic shutters. This feature has been helpful for macro photography and anyone working on a tripod who wanted to eliminate any possible vibration at the start of an exposure.

Starting with an electronic exposure appears to be quite different to ending with an electronic exposure. Turning on pixels seems to happen very quickly, but turning them off may take longer; hence why the closing shutter needs to be done mechanically to avoid distortion of moving subjects.

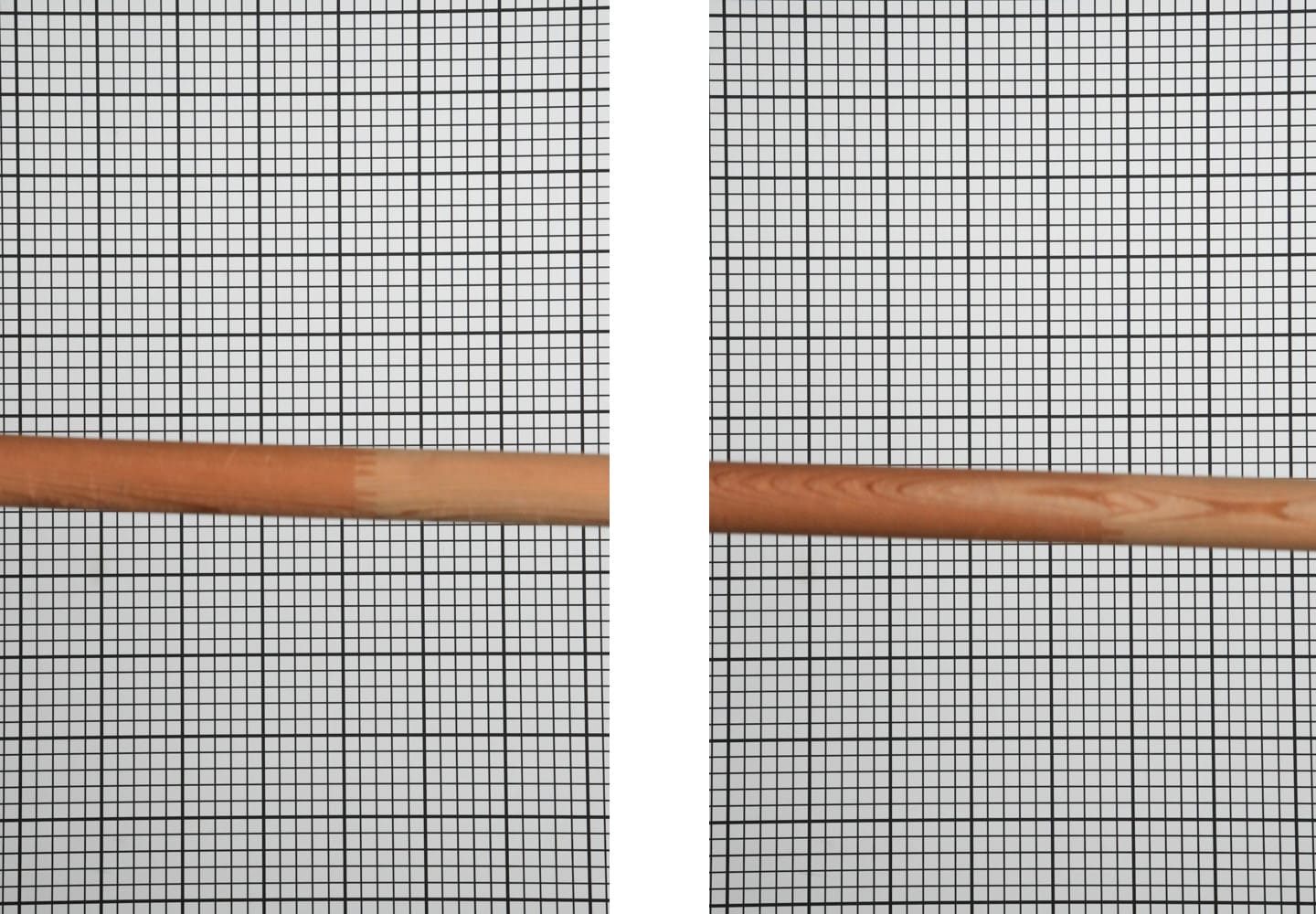

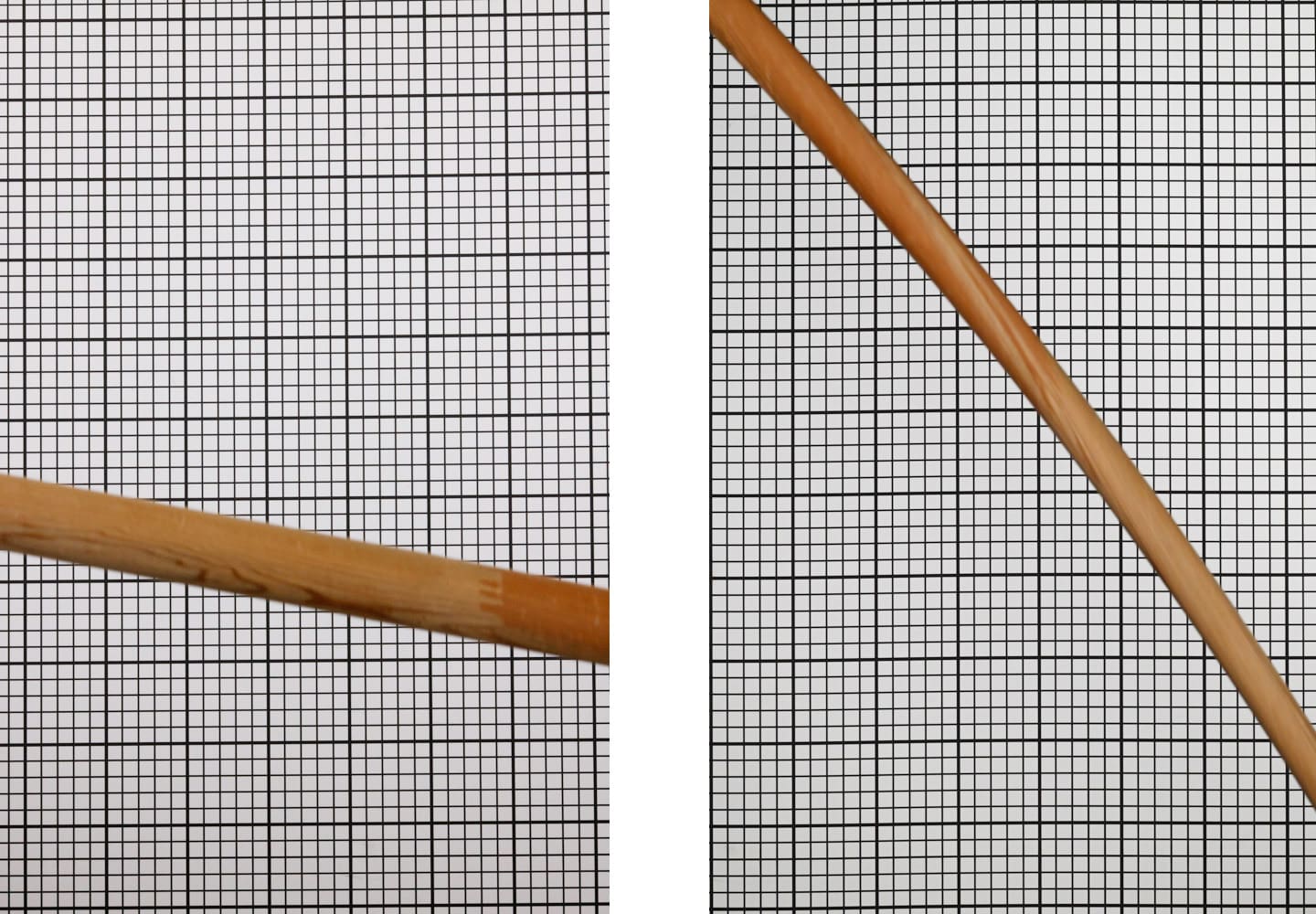

The distorted grid is caused by the electronic shutter and panning the camera quickly from right to left.

New Technology

A breakthrough in processing speed was made with the stacked CMOS sensor, allowing for faster read speeds. The first camera to significantly speed up the digital scanning process was the Sony A9 (2017). It was the first camera you could use the full electronic shutter to capture moving subjects with little to no distortions. This was improved upon with the Sony A1 (2021) and again with the Nikon Z9 (2021).

In recent tests that I’ve developed, I’ve been checking to see how distortion free the new electronic shutter of the Sony A1 really is. In my test I drop a wooden dowel across the frame of a vertically mounted camera. In theory a perfectly fast shutter would record the wood stick as a straight horizontal line. In the real world this is not possible because with both mechanical and electronic shutters, there is a scanning process across the frame. If the scan moves from left to right, it will record the stick first on the left and then as it moves to the right the stick will continue to drop; the faster the scan, the straighter the stick.

Left: Sony A1, Mechanical Shutter, 1/2000 sec.

Right: Sony A1, Electronic Shutter, 1/2000 sec.

Using a shutter speed of 1/2000 second as my testing standard, the best you can hope for is a minimum of distortion. With the more than dozen modern cameras used in my test, the mechanical shutter from all of them looked pretty much the same; minimal, but barely noticeable distortion. Using the electronic shutter, it’s a very different story.

Left: Canon EOS R5, Electronic Shutter, 1/2000 sec.

Right: Nikon Z5, Electronic Shutter, 1/2000 sec.

The A1 and its full electronic shutter is indistinguishable from the mechanical shutter. Nikon says that they have surpassed the A1 in speed: impressive. But I can’t imagine how it will make a tangible difference over the A1 for any photographer. These cameras, along with the new Canon EOS R3, look like they’re the first in a new generation of cameras. With these three cameras, and more to come, you’ll be able to use the electronic shutter for everything.

I’m sure future cameras with silent shutters will offer a digital “click” sound that you can turn on in the menu should you need an audible confirmation. But, it’s just not the same.

At a recent sporting event I decided to shoot with the Sony A1, set to use the electronic shutter. It took a bit of practice to get comfortable with the silence. Without the audible confirmation I was less aware of the number of images I was recording, and thus ended up with far more images than was needed. I’ll need to keep a closer eye on the frame counter next time around.

The electronic shutter allows for very fast frame rates, providing you with the opportunity to capture the perfect moment.

[Sony A1, Electronic Shutter, 1/1000 sec.]

Klickensenomore

Here’s a favorite story from my early days at the camera shop. A tourist comes in to the store and uses halting english to try and describe a problem with his camera. He keeps repeating the phrase “Klickensenomore.” After a few times going through the same motions, we determined he was saying that his camera – clicks no more.

So are you ready to click no more? I’m guessing that I’ll mostly adopt the silent shutter. In some cases it will be a superior way of shooting. In certain circumstances I think I’ll want that feedback that comes from that ever so simple “click.” My question now is whether I may have a choice of clicks. Imagine being able to select from a collection of your favorite sounds. Do you feel like a solid thunk of the Nikon F2 or the discrete click of a Leica?

Do you have a favorite “click” memory?

Become part of John’s inner circle

Sign up for the newsletter here – it’s free.

Want to become a better photographer?

Check out John’s selection of photography and camera classes here.